1

This essay is a failure. Because all essays are, if you subscribe to a certain theory of writing as a failed attempt to express ideas, thoughts, emotions, all that ethereal stuff we’re tasked with expressing. Or not—maybe you’re into repressing that shit.

I used to tell my students that “essay” means “attempt,” which I hoped would help them relax when asked to do some writing. Dream on!

Having an Instagram account and not a real idea of why, I’ve followed many a hashtag, among them #samuelbeckett. As a result, I’ve seen plenty of photos of the ultra-photogenic writer, as well as countless uses of this quote from Worstward Ho: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Beckett’s “Fail better” is often used to make people feel good about fucking up. The larger quote usually comes accompanied by motivational poster imagery: flowers, sunrises. . . one expects a cat holding onto a rope will pop up at any moment. Hang in there, Baby, and fail better!

All this sunshine runs contrary to my reading of Worstward Ho, a text that seems to want its reader to reach for the bottom. But who cares about authorial intent? Clearly not the Silicon Valley gurus who’ve hijacked Beckett’s words.

2

I am not one to use the Beckett quote in either the overly simple Fuck it, let’s jump into the abyss sense or in the manner of the startup tech bro. Mostly, I try not to use it, as the quote is so divorced from its source that it’s in danger of losing whatever meaning it may have had. (Ironically, this loss of meaning may be in line with Beckettian ethos. Sam has his revenge.) I do think often, though, of another quote from Beckett: “Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness.”

Of course, as Art Spiegelman pointed out, Beckett said those words.

There’s the rub: to express ideas, we need language, even when the idea is that language is both a mere attempt (often a failure) and an assault on silence. This seems the kind of Zen contradiction monks might meditate on, and I’ll not go too far down that road, but suffice it to state that Beckett was onto something. Language solves as many problems as it creates. At least we hope it does.

3

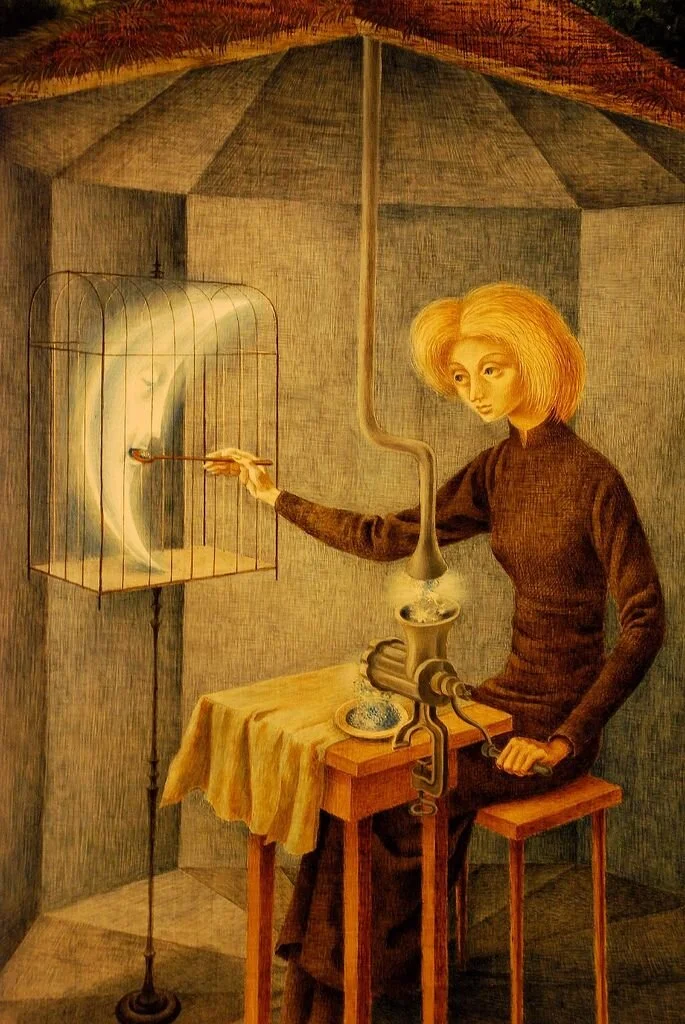

All this is a long way of introducing my real topic: my inability to express my feelings about visual art without sounding like a ninny. Inspired by my Facebook post of a painting by Remedios Varo that I shared along with the proclamation: “My favorite thing about not studying visual art is that I lack the words to convey why I like the stuff I like. And I like Remedios Varo,” it was suggested (Hi, Billy!) that I try to write about an art form outside my wheelhouse. I’ve studied literature and writing; I’m an autodidact when it comes to film and music—in short, while hardly an expert, I feel capable of discussing literature, film, and music. But not painting.

I love visual art. I have favorite painters (Francis Bacon, Ivan Albright, Max Ernst, Marc Chagall, Gertrude Abercrombie, the before-mentioned Remedios Varo). The Art Institute of Chicago remains my most beloved spot in the city. I love the big dead Jesus renaissance stuff. I love the conceptual pieces that piss people off. Dadaism still excites me. I’ve defended that big all-black canvas called “Painting” against claims of “Well, I could do that.” Rothko’s blurry red cubes? Love ‘em. Bruce Nauman’s Clown Torture? Applause! And I even love the hazy Monet paintings, all but those damn wheat stacks. Mexico’s muralists, Russian propaganda posters, Italian Futurism. . . all of it wonderful! I love it all (except Primitivism— fuck that colonialist condescension).

But that’s about all I can say. If I look at the Varo painting I shared on Facebook and try to explain why I like it, I fail. First stabs at forming a recognizable idea are aimed at the technique, as if I know anything about that. But I can see deliberate brushstrokes, shading, attention to what light does to a human form. Clearly Varo is adhering to some traditional representation even if she juxtaposes dreamy surrealism— the caged moon and celestial meat grinder. I immediately make a connection to the work of René Magritte who wanted to be a surrealist but wasn’t going to stop painting men in hats. You can melt some clocks or you can proclaim a perfect looking pipe is not a pipe. There’s more than one way to skin an oboe.

So, I’ve stated my love for specific artists and movements, and I’ve done a very small amount of thinking/writing about the Varo painting. None of this would get published in Artforum, though, would it?

4

My inability to properly articulate my appreciation for visual art bothers me not a whit. I’m not so thoroughly academic as to dissect art to the extent that its parts are laid out neatly for my understanding, but considering I teach composition and the occasional literature class—and that I’ve written two books in a sort of “Look at me! I’m a writer!” gesture—I do recognize some of what’s going on in a piece of printed material. I often wonder, Why did this writer do this? Why resort to an easy metaphor? Oh, this is a fresh approach to internal dialogue. But isn’t this paragraph bordering on purple prose? Oh wow, haven’t seen that before. Look at this deliberate lack of punctuation—someone thinks they’re Kerouac. I was listening to a podcast the other day where the important man being interviewed failed to name Neil Postman as the source of three of his ideas, and it drove me fucking mad. I’m not the most widely read dude, but I read as much as I can. I like recognizing references, seeing the progression of thoughts and the signaling back to past works and concepts, and yes, spotting when podcast guests fail to credit their obvious influences. I like to know about books and writers and have something to say about them. And all of this. . . I guess I’ll call it “training” has (thankfully) not robbed me of the pleasures of the well-written book, story, essay, or poem, but I do admit to having enough of an understanding of what’s under the hood to see what a writer’s doing.

I have no such insight when it comes to visual art.

I’m not a musician, but I fuck around on guitar. I took lessons in high school and played in garage bands and even in front of people at parties, but my skills never evolved past basic chords and scales. Still, when I hear some rock songs, I know what the guitar player is doing. I know enough to talk, often pompously, about why some guitarists are overrated (looking at you, Clapton) and who I think are the best alive (Robert Fripp and Andy Summers). I can invoke the Aeolian and the Phrygian modes and smile when people talk about Jack White’s genius all the while silencing the part of me that wants to say, “Fuck that guy—listen to Greg Ginn or Jim Hall or fucking Django Reinhardt!”

But with visual art. . . there’s still the magic of not understanding. I don’t know much about craft, and whatever history I’ve studied is limited. Because I don’t really care about the academic side of it all— I just love the stuff I love, probably because I don’t always “get” it. Or I get something, but that something eludes perfect description.

Okay, here are a few thoughts from two movies:

In an underrated movie from the world’s most overrated filmmaker (and big time creep), Woody Allen’s Another Woman contains a scene where Gena Rowlands’ character meets Mia Farrow’s in an art gallery. The Farrow character is weeping at the sight of a Klimt painting. Rowlands’ character, an academic, tries to tell the crying woman that she ought not to react that way— this is from a very happy period of Klimt. The academic is attempting to stifle a sincere emotional reaction to a work of art. Why? Because the academic’s big brain knows about the painting, whereas Farrow’s character is simply reacting. How often does this sort of thing happen? Are we trained by, and as, academics to detach? Possibly. I’ve met people who’ve said that grad school made them never want to pick up a book again. I know English majors who graduated and never read anything other than the occasional celebrity memoir. I made it out of grad school with my love of literature intact, so it’s not like all of us suffer such a fate. Still, there is something to this example from Another Woman, the emotional confronted with the cerebral, that sticks with me. What has Rowlands’ character, with all her erudition, lost? Is there a Gena Rowlands and a Mia Farrow in my head, always battling it out? Do I too often dry the honest tears of my inner Farrow and let Inner Rowlands go on talk talk talking?

There’s a good chance I’ve seen Monster’s Ball, but all I remember is that a guy on death row sketches people and says, as criticism of the camera, that it takes a human being to see a human being. This may be why I react more strongly to painting than photography. This may be why I respond to the art that I respond to, even if it’s not portraiture: a painting is a human’s unique view of something rendered carefully through a process I don’t really understand, made available to all for their engagement or lack thereof. But through that rendering, something more than the subject is revealed.

If we believe—and I do—that writing exposes something about the writer (shattering the myth of objectivity), why not use the same idea to understand visual art? Not a mind-blowing concept I grant you, but this is where my head is, where I might start to articulate my love for Varo, Bacon, Albright, and all the other artists I admire. Each of these painters would see a shared subject differently. Their art is a form of communication, of the subject and of themselves. Which is why I love their work, but also why I grapple to communicate that love, being trained since birth to use words in a way that, honesty, feels criminal the older I get.

5

Here goes:

I turned 50 recently. No big deal, really. If reaching the half-century mark did anything it was to remind me that I don’t give a fuck about birthdays. And I’m in better shape—physically and mentally— now than I was at 25, so I find it hard being weepy about “getting on.” Nevertheless, I’ve not escaped all of the existential thoughts that come with this “milestone.”

A lot of my thinking lately is on the impossibility of language, the before-(inadequately)-mentioned ideas born of a mangled reading of Beckett and my own simple-headed view that language is a con.

At risk of pissing off potential readers, especially fellow writers who know better than to use the 2nd person POV, let me ask you a question. Have you ever been struck wordless by a work of art? Because I have.

The first time: after watching Mike Leigh’s film Naked in 1993 at the Three Penny on Lincoln Ave. My friends all wanted to talk about it. I had no words. The movie was that devastating. And I found myself annoyed at these people who felt the need to immediately examine the movie, to have an opinion—the “correct” opinion. Fuck me, can we just take a minute to let it all sink in, to process the feelings the movie conjured? Can I pause and come to grips with my own complicated reaction? Forcing words felt wrong, stupid.

The first time I saw Ivan Albright’s That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door) at The Art Institute, I was again silent. The person I was with made comments. Look at the attention the artist paid. Albright used brushes trimmed of all but two of their hairs to get some of the tiny details. He was meticulous, you can see. Blah, blah, blah.

Still my favorite painting, I can’t say much about That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door) except, well, that it’s my favorite painting. Maybe deciding on words to describe the painting would ruin it? There’s magic here, people. Why the fuck would I want to kill that?

In his intro to Anne Sexton’s Transformations, Kurt Vonnegut shared a story about quitting teaching when he realized it was criminal to explain works of art. He’d been tasked with lecturing on Dubliners and found, as he was in front of a room of students, he had nothing to say. Not because he disliked the book, but because, again, it felt wrong to reduce such an achievement through whatever lecture he’d planned. One might say this is a cop out, but I get it.

Which brings me to another example of the difficulty of discussing powerful works of art. Roger Ebert reviewed 2001: A Space Odyssey and used plenty of words, but I only remember his quote from E. E. Cummings “I’d rather learn from one bird how to sing / than try to teach ten thousand stars how not to dance.” The idea being that Ebert was happy accepting the mystery of Kubrick’s film, recognizing that over-analysis would kill the magic. Sometimes you have to leave the stars alone and just appreciate how beautiful they are.

Years later, when 2010: The Year We Make Contact was released for reasons I’ll never understand, Ebert referred again to the Cummings poem and said that the unnecessary sequel tried to teach ten thousand stars how not to dance.

But here’s the thing I’m just now understanding: Ebert used a poem to discuss 2001, and again in his review of 2010. He may have been speaking to the problems with over-analysis, but he still USED WORDS.

Which sorta brings me back to the point of this section of this essay: I’m losing my faith in words. Ebert didn’t— motherfucker kept writing to the very end. And Vonnegut, despite his wordlessness regarding Dubliners, wrote plenty, even later in life when he seemed more interested in his visual art. Critics abound— no one, be they learned or ignorant on their subject, is shutting up anytime soon. And maybe they shouldn’t. (Maybe?) Even when we feel speechless in the face of beauty, truth, or whatever the hell it is about a work of art that challenges, we should likely try to say something. I mean, we can’t just go, “Uh. . . wow. . . like. . . whoa.” For fuck’s sake, I pass myself off a writer and I can’t write about this subject? Really, Vince. Fuck off, dude. And what’s this shit about the failure of language? It’s been working pretty well for a lot of years, the exact number you could easily google but you’re too lazy and, fuck it, you’re flowing now, aren’t you, adding words words words to this already long (2,558 words, as of this moment—whoops, it’s grown to 2,567) essay, flowing and spouting and writing and thinking and feeling compelled to share these thoughts because it’s soooooo important that it all be shared and that you land on some terra firma in this otherwise abstract clusterfuck of a blog post like it fucking matters and anyone gives a goddamn.

Sorry. I can get a little combative with myself.

Perhaps the best I can do is conclude that however much I write, and regardless of the hours I might spend thinking about this stuff, I’ll never really feel comfortable with my ability to state what I feel about many subjects, not the least of which is visual art. I mean, do I really have anything important to say on the things I feel comfortable discussing? No, not really, but has that stopped me from flapping my gums? Nah. So I can live with the failure. Because what would be the point of succeeding, anyway? If one were to actually say the perfect thing about a painting or book or song or whatever, they’d win the game. No point thinking about it anymore. Where’s the fun in that?

6

Best art criticism I’ve ever heard came from my boss at the bookshop where I worked in the 1990s. He summed up his appreciation for the Dadaists and Surrealists this way: “They looked at the Impressionists and the shit that came before and said: ‘Blow it out your ass!’”