Two Doctors, Columbus Ohio Public Library

Maybe 1984? I don’t remember when, just that I’m a kid, a youngin’, rugrat, pudgy little weirdo who has maybe read a comic or two before, but Dad decides a trip to the library is a good idea, mostly because he wants to exchange whatever he’s read for another book. And yeah, I know there are these places called libraries—each elementary school I’ve attended has one, but they’re places where we play more than read books or do anything serious, except for the library in the Catholic school I went to from first to third grade. They didn’t have a library, or maybe they did? There was that room with a few books and a desk, but it was nothing like the library at my next school or my current school, Wilkins Elementary, where I’m currently enrolled yet on reprieve, this being summer.

I spend summers with Dad because he and Mom are divorced, the best thing to ever happen in my young life not because the divorce ripped our family apart and took me and Mom and the big brother to the Chicago suburbs and left Dad in Ohio, no, I love Dad and don’t want to be away, but, you know, what would they have been if they’d stayed together? A train wreck, right? Fuck if I want to wake up to fighting parents who don’t understand that sound travels the short distance from the kitchen to their child’s bedroom.

So there’s Dad taking us into this place with rows of books and desks, like the school library but bigger, and he’s telling me and the big brother that we can check out whatever we like, encouraging us, really, Go ahead, pick out something, and I find a book on Vincent Van Gogh who I’ve decided I’m interested in because we have the same name, though all I know, and all I want to read about, is that this madman cut his ear off. Tomorrow I’ll skip to the end of the book and look for that, because he must’ve cut it off late in life— can you even survive that? Won’t you bleed out? I’ll be let down when little of this book discusses the gory self-mutilation, focusing instead on brushstrokes and shadows and things I know nothing of, but I’m getting interested, maybe I should become a painter?

The big brother is getting a book on sports. Dad’s is about some president who’s dead by now. He assesses the three texts as we check out and says, “Well, this is a paradox,” and I don’t know the word but I’ll look it up later and wonder if this is the right context, if a synonym might’ve worked better, but no, I’ll not think that because I’m a kid and what do I know? Instead, I’ll ask another adult, “What’s a paradox?” and they’ll answer, “Two doctors.”

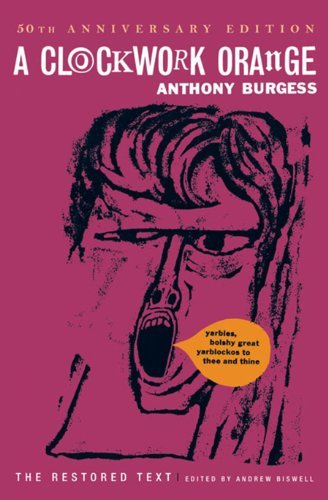

A is For Addict. Bridgeview Public Library

Though I’m too young for it, I’ve seen this movie A Clockwork Orange and found a book by the same name in the Waldenbooks at Chicago Ridge Mall. But I decide that living a few minutes from the Bridgeview Public Library has its advantages, one of them being I don’t have to sacrifice my allowance money, which I’ve not really earned, to the corporate mall bookshop, though I’m too young to care about class warfare and am not engaging in critiques of capitalism or anything so academic, no, I’m just looking for a free book that might be as good as The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the book my stepdad told me was a lot of fun, and he was right, read it, read the next few books in the series, the so-called trilogy that is now up to four books, another coming before the author kicks the intergalactic bucket. A Clockwork Orange should be as fun, right? If the movie is any indication, yes, indeed, absolutely.

The librarian is not thrilled to explain the Dewey Decimal System, really just how to find the card with the call number and how to use that breadcrumb to find the hiding Hansel and Gretel, mixing metaphors maybe? Sorry. Ahem.

There is it, at last, after missteps and distractions and near-giving up, I see the book by Anthony Burgess, nice and clean but smells musty, a scent I’d soon be used to, maybe even fond of, though it’ll someday cause conversation with cohabitors about the stink of old books clouding up the air in here, what the hell?

According to the intro to the book, the author was not fond of the movie version. And there’s a last chapter in this novel that the movie ignored. Suddenly I get what the teachers have been saying, that the book is always better, that there’s more to discover in pages than what celluloid has to offer, the director and producer and actor having stepped on the text. This shit is pure! What a rush. I’m hooked.

Cynical Bastard, St. Laurence High School Library

I’m mistaken for someone with a similar name, odd considering no one else has my name, but she’s old this woman in the library, and so when she asks me to assist her, I ought to be a “nice little lamb,” as my English teacher calls his students, but I’m not in the mood and am already concocting some bullshit about being late to class. Have I responded too roughly? Apparently so, but she thinks I work here, is, yep, mistaking me for some student employee whose last name is not really that close to mine, maybe we share the first five letters, an honest mistake— she’s new.

However sassy or otherwise my refusal, it makes no difference, because I’m in hot water, doesn’t matter that she made the mistake or that I may have been busy and late to class (not really). No, what matters is that I’m rude to an adult, a superior, not a Brother or Teacher, but someone nevertheless above me, which is pretty much everyone at this school. So later, when Brother M. catches me in the hall and chews me out, which I suspect he’d like to literally do (or is that figuratively? Not sure, but he wants to get part of me in his mouth, fucking perv, ass grabber), well, I’m a little taken aback and try to explain that she thought I was he, not me, not a kid using the library to study, no, she thought I worked there, but he’s not having it.

“You don’t speak to her that way,” he says, then calls me a “cynical bastard,” and I have to ask Mom what that word means. “Cynical,” not “bastard”— I know that word.

The Way of All Texts, Moraine Valley Community College Library

I don’t think there will ever be a library I’ll love more than this one, where I’ll spend more of my free time, this fountain in the basement floor is a perfect place to sit and read most of Prizzi’s Honor and a lot of The Godfather— I’m into mafia books at the moment— and none of them books I’m supposed to be reading for class, none of them being “classroom appropriate.” Except for Vonnegut, who I’ve just discovered and who my comp teacher likes, so much so that he asked me, “Which class is that for?” when he saw me reading Slaughterhouse-Five, and when I said, “None,” he was impressed, and yeah, it felt good because I’ve never impressed a teacher before. I’m doubly floored that this comp teacher, Mr. S., has gone and incorporated Slaughterhouse-Five into the lecture, because he loves the book enough to have ready-to-go thoughts, which makes me realize that teachers sometimes just riff, improvise, ad-lib. This is the most informative and perhaps destructive moment of my training, as I will often do exactly that: riff, improv, ad-lib when teaching my comp classes, not always a good idea.

Years later, when I’m an adjunct instructor at this very same junior college, the library will not seem so grand. I’ll not find the fountain, and the stacks will have diminished. The whole place will seem more sterile, the result, no doubt, of renovations but also, sure, because computer screens are eating up some of the space once dedicated to books. The way of all flesh, right? And texts.

Don’t Belong, John T. Richardson Library, DePaul University

My girlfriend has a job at the library. I like this building, but I’ve not been in it much, preferring to spend the trimester smoking cigarettes and drinking malt liquor like the young idiot that I am. She does neither of these things. She likes staying in, going to bed early, reading shitty books by the likes of Jude Deveraux and not taking an interest in the Kerouac and Orwell and Bukowski (so many dudes) books that I’m digging, edgy shit, man!

She works late (for her) and I escort my gal from library to dorm, a short walk but she’s worried, this being the big bad city. Sometimes I go up to her room. Most nights I leave her safe and sound at the door and then I find my friends and we drink malt liquor and smoke cigarettes and talk about Kerouac and Orwell and Bukowski (and Godard and Polanski and Fuller) and think we’re smart, that no one has ever had these brilliant thoughts before. But we’re idiots. And none of us has been in that library, most of all me.

If I spent any time in that library I’d notice that my girlfriend has made fast friends with a blond-haired, blue-eyed, possibly British grad student who also works there, who has more than charmed her, who she’ll not leave me for so much as think about when we’re together and I’m boring everything but the pants off her. And we’re soon to go kaput, which surprises neither of us, but, you know, never a great feeling. It’s okay, though— I don’t belong in this relationship, this school, certainly not that library.

Solace, Schaffner Library, Northwestern University

Word on the street is that it’s not long for this world, another casualty of the pandemic, though I’m sure the axe has been sharp for some time, this being not the biggest library on either campus, but that’s maybe what I like about it, that and the little room on the second floor where I worked as a tutor, a quiet space near the stacks with a window overlooking a courtyard and a computer to write my poems between tutoring sessions. As a grad student intern who’s been tasked with making a mock-book of international poetry for this big ol’ anthology, I roam the bigger stacks in Evanston and pull Milosz and Szymborska and a few other Polish poets (the editor has his preferences) along with the cursory Celan and my latest discovery, the superb Amichai. I’m awash in poems, my own stabs and the polished gems that’ll comprise this book I’ll have a small hand in birthing, the education in international writing is better than the one I’m paying for.

Years later— I can’t let go of the gig, so it’s back to Schaffner until I can get some semblance of a career going, though I suspect that I could stay in that room on the second floor, among the smaller but no less significant stacks with the view of the courtyard, indefinitely, typing wayward poems in the minutes before my next tutee arrives panic-faced with no idea what the professor wants from them.

Anything, Saltzer Regional, Chicago Public Library

I come here on my lunch break and read and then, because the time moves too quickly, eat a fast sandwich while driving back to work. I come here on my lunch break because it’s beautiful upstairs at the long table with the big clock and the feeling that I could be anything.

Get Off My Lawn, Murray-Green Library, Roosevelt University

I walked to the back of the library as an undergrad who’d taken more than a few years off. I was an “adult” and more receptive than ever to the idea of a quiet space full of books, though today, even more adult, employed as lecturer and Faculty Coordinator of Writing Tutoring at this very same school that took me in after desultory years of fucking up, I can’t help but lament the space sacrificed for activities and computers and offices and things other than the old stacks, though some remain, sure.

I’ve made it a point to take my class here, to show them that yes, we still have a library with books and that there are wonderful things and wonderful people here, that they should make the library part of their routine. One of the students expresses grief at the “dead trees”— “All I see is a destroyed forest,” he says, and I ask if he prefers to read on his computer screen, which no one can possibly prefer, but he says he does, though adds that he only reads when he has to, no shock and not anything for me to waste time on, seeing as that is hardly a new problem. But I’m tempted to lecture that books hold a certain value that he’ll not get elsewhere, that libraries are important places, that they represent more than dead trees and dead writers and dead ideas, that they don’t actually represent any of that, that they represent community and scholarship and thought and emotion and life and love and war and hate and discourse and rhetoric and exploration and engagement and humility and desire and tradition and radicalism and socialism and capitalism and egalitarianism and a lot of other isms and that he should see a library as the effort to preserve these things as well as a place to work, study, think, laugh, socialize, mobilize, organize, antagonize, and maybe even better himself and melt into the collective betterment of the fucking world. I succumb briefly to this temptation. An old man shaking his fist. Hoo hum.